The brainers

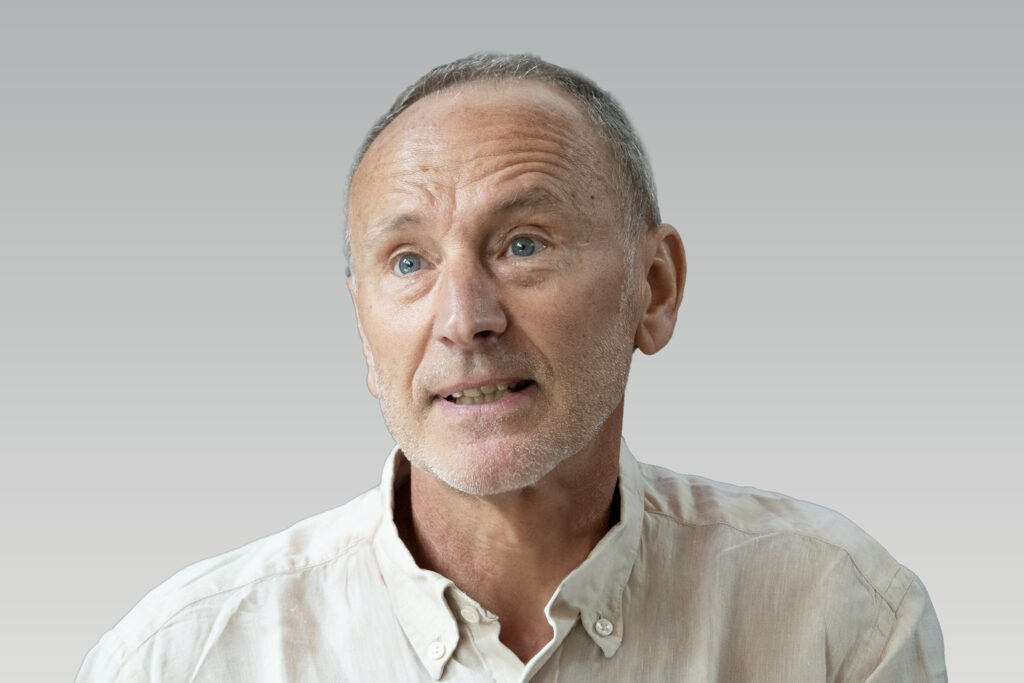

Thierry Pozzo – Neuroscience researcher

Thierry Pozzo is Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Burgundy and Honorary Senior Member of the Institut Universitaire de France. His research project involves studying the organizing principles of human motor skills and identifying the underlying physiological mechanisms. The lines of research developed take into account recent advances in neuroscience, which suggest a close coupling between Action and Perception. It supports the hypothesis that cognition is rooted in the bodily experience of individuals and depends on the motor system, contrary to the metaphor of the calculating brain. Finally, the narrowness of these questions and the standards imposed by science have convinced him for several years to extend his thinking to the field of image perception and the reciprocal contaminations between Art and Science. This part of his activities takes place within the framework of the organization of popular science events at the Espace Marey, a platform partly dedicated to promoting the work of the Burgundian scientist of the same name.

This brainer takes part in round-table discussions, offers improvisation sessions and the following solo talks:

Is living matter essential to the construction of reality?

Since the 1980s, a silent revolution has shaken up our knowledge of the brain and cognition: thinking, perceiving and acting are no longer considered solely as cerebral states using language and logical-deductive reasoning, but as the implicit mental manipulation of actions. In other words, Action, Cognition and Perception are based on shared mechanisms and nervous substrates: thinking means replaying a lived experience; recognizing an object before naming it means evoking the sensory effects of its use. The body is not a set of peripheral accessories, effectors at the end of the decision-making chain, as in the parable of the slave who molds the brick according to the master's recommendations, but the body is matter and thought. Indirect proof of the body's continual presence in thought is the case of the phantom limb. Even when the amputation of a limb deprives the body of matter, thought reconstructs it mentally. But is perceiving and knowing constructed solely within living matter? How do these armless, legless machines perceive and experience the world? In other words, is a bodiless (artificial) intelligence possible?

Does style determine motor performance?

The development of movement sciences in France over the last 20 years has undoubtedly led to progress in the training of top-level athletes. The academic recognition of this discipline has been possible thanks to the contribution of other, older fields of research, such as those belonging to the inert sciences. These links have enabled us to develop systematic reading grids and a modelled approach. However, the downside of this enriching proximity is that it has encouraged the standardisation of observed phenomena and helped to erase inter-individual differences, which are often regarded as measurement noise. One of the aims of this conference is to convince the audience that describing motor skills in terms of general motor laws is a limitation to our understanding of living organisms. Doesn't sporting excellence translate into a singular production of movements and a style that makes the champion and sets him or her apart from the ordinary tendency? Can the analysis of qualities and singularities complement that of quantities? Is it possible to envisage a conception of sporting performance that avoids prototypes?

Cognition rooted in the body

Diderot wrote: "There was a natural man: an artificial man was introduced into it, and a civil war arose in the cave that lasts a lifetime". One Western tradition sees the sensory consequences of action as the world below that stands in the way of reason. A different perspective, based in part on experimental neurophysiological evidence demonstrating the structuring role of voluntary movements in decision-making, learning and knowledge, is nonetheless conceivable. During this talk, the 'I think, therefore I am' (Descartes), which isolates thought from lived experience, will be confronted with the 'I am my body' (Merleau-Ponty), for which cognition begins with sensory-motricity.